Music theory doesn’t have to be intimidating. In fact, understanding just a few key concepts can completely transform how you approach the guitar, opening up creative possibilities you never knew existed. These aren’t abstract academic ideas—they’re practical tools used constantly across all styles of music, from pop to jazz to rock.

Today I’m breaking down five essential music theory concepts that every guitarist should know and which will make your rhythm guitar sound amazing. Each one is immediately applicable, sounds beautiful, and will make you a more creative, confident musician.

Concept 1: Secondary Dominants (Leading Chords with Purpose)

Secondary dominants are one of the most powerful tools in music, and once you understand them, you’ll hear them everywhere. They’re used constantly in every style of music to create smooth, compelling chord progressions.

The Problem They Solve

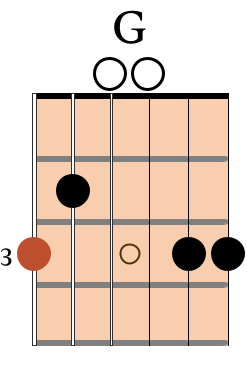

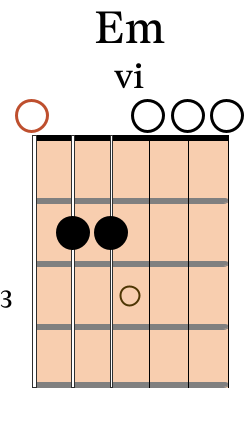

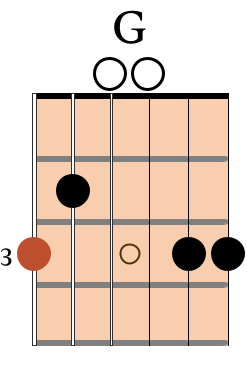

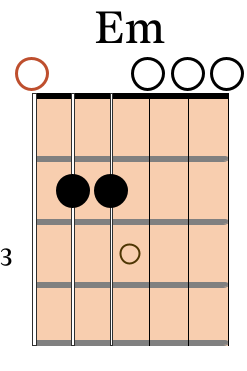

Let’s say you’re playing two basic chords: G major to E minor:

It sounds fine, but it’s a bit plain.

There’s nothing particularly exciting about this movement. But what if we could make that transition more compelling—more purposeful?

And this is where secondary dominants come in.

What Is a Secondary Dominant?

A secondary dominant is a dominant seventh chord (V7) that leads to a chord other than the tonic. This makes the target chord feel like home —even if it’s not the actual tonic of the key.

To find the secondary dominant of any chord all you need to do is count up five scale degrees (or down four) from that chord’s root, and build a dominant seventh chord there.

This might sound complicated, but it becomes easier to visualize with a few examples.

Secondary Dominants in G Major

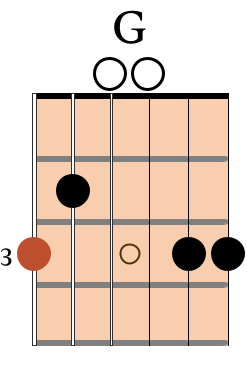

In the key of G, we would start with the chord of G as our tonic:

From this tonic chord, you can then approach any diatonic chord with its secondary dominant:

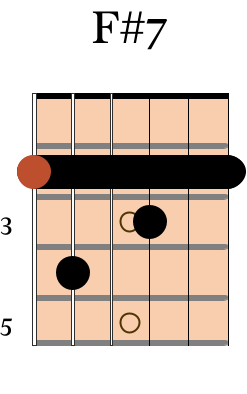

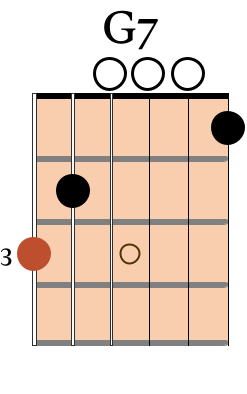

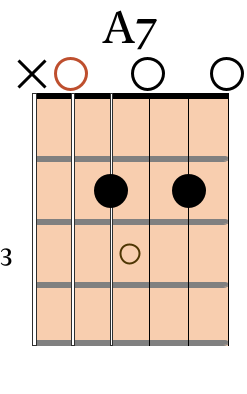

↓

↓

↓

↓

↓

This creates beautiful chord movements and adds new colors to your chord progressions.

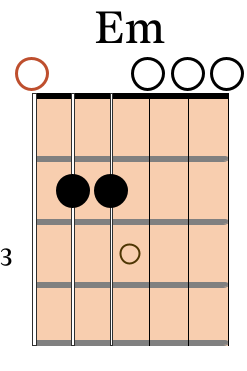

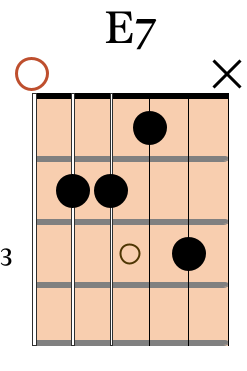

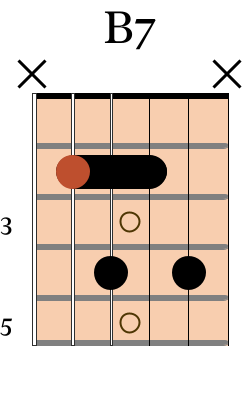

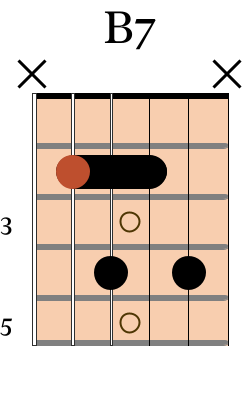

The Classic Example: G to E Minor via B7

Let’s apply this to our opening example. Instead of going directly from G to E minor, we’ll insert B7:

Suddenly the progression has direction and purpose. The B7 creates tension that resolves beautifully into E minor. This is called a secondary dominant to the vi chord (the six chord).

Why It Works

The dominant chord (in this case, B7) is the V chord in the key of E minor. Even though we’re actually in G major, we’re momentarily borrowing from E minor’s harmonic language. This creates a brief feeling of “going home to E minor” before continuing in G major.

The concept is called “secondary” dominant because it’s not the primary dominant. In G major, the primary dominant is D7 (the V chord that naturally resolves to G). All the others are secondary dominants—they lead to chords other than the tonic.

Concept 2: Inversions (Same Chords, Different View)

Inversions are one of the simplest yet most effective ways to add sophistication to your playing. The concept is straightforward: instead of always playing the root note in the bass, you rearrange the chord to put a different note on the bottom.

The Basic Progression Problem

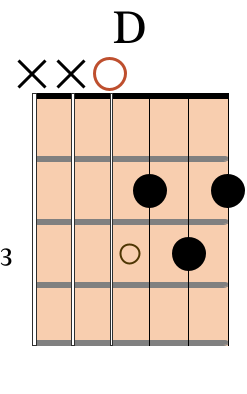

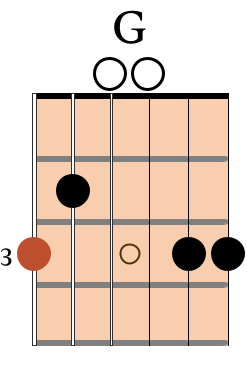

Let’s start with something incredibly common: D major to G major:

This has been done a million times. It works, but it’s completely predictable. We need something to spice it up.

Enter Inversions

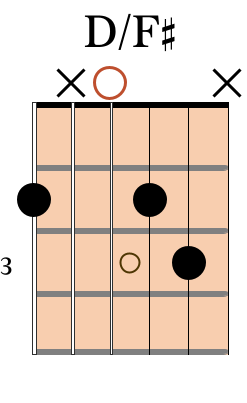

An inversion simply means taking a chord tone other than the root and placing it in the bass. For a D major chord (D-F♯-A), instead of always playing D as the lowest note, we could use F♯ or A.

Here is what the chord looks like when we put the note of F♯ in the bass – turning it into a D/F♯:

If we apply this to our D-to-G progression and play D/F♯ → G, the movement sounds much more connected. The bass line moves smoothly from the note of F♯ to G.

This is known as “voice leading” and creates an elegant sound, especially compared with jumping between the D and G chords. creates much more elegant voice leading than jumping from D to G.

Freedom with Inversions

The beauty of inversions is their flexibility. You’re not disturbing the harmonic progression—you’re using the exact same notes from the chords. It’s the same musical world, just viewed from a different angle. Different sauce, same ingredients.

You can throw inversions in whenever you want because you’re not adding any “wrong” notes. You’re simply reorganizing what’s already there.

Inversions are particularly useful for:

- Creating smooth bass lines in progressions

- Avoiding large jumps between chords

- Adding sophistication to simple progressions

- Solo guitar arrangements where you want melodic bass movement

Concept 3: Extensions (Added Colors to Chords)

Extensions. The word alone can sound intimidating, but it shouldn’t be. All an extension means is an added color note to a chord—nothing more, nothing less.

People sometimes get scared when they see chord names like Cmaj9, D7♯11, or Am11. Those numbers seem complex and jazz-theoretical. But here’s the secret: extensions are just scale degrees added on top of basic chords.

Chords & Numbers

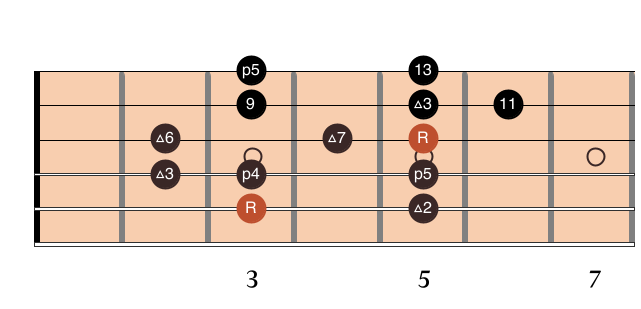

The numbers in chord names refer to scale degrees. So in the key of C major you have:

C(1) – D(2) – E(3) – F(4) – G(5) – A(6) – B(7) – C(8) – D(9) – E(10) – F(11) – G(12) – A(13)

This is what it looks like on the fretboard:

So when you see:

- 9: It’s the 2nd note, up an octave (D in C)

- 11: It’s the 4th note, up an octave (F in C)

- 13: It’s the 6th note, up an octave (A in C)

This might sound complicated, but it is easier to visualize with an example.

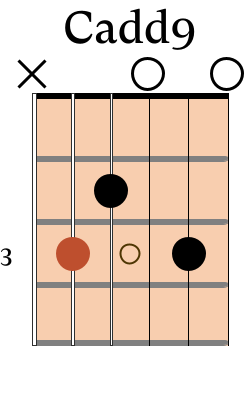

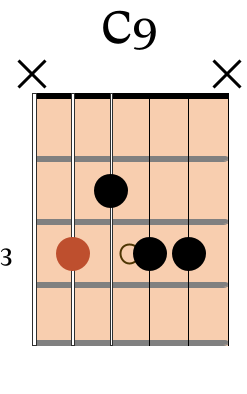

Let’s take a basic C major chord—the shape everyone knows. To make it a C9 (or Cadd9), we simply add the D note on top like this:

That’s it. Extensions are just added color. They make chords sound richer and more sophisticated without fundamentally changing their function.

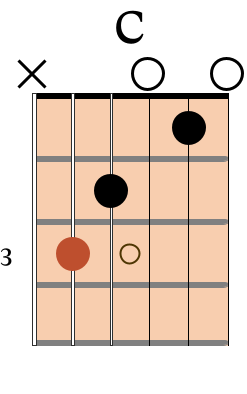

In this way you can take any chord and adjust it by adding scale degrees:

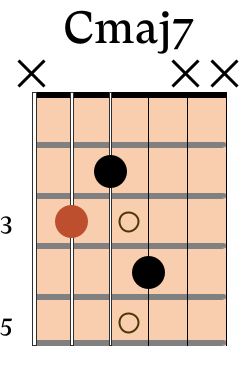

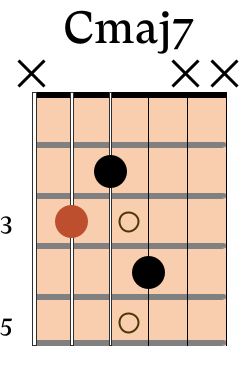

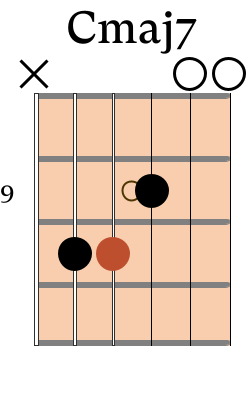

In this first example, C has been turned into Cmaj7 by adding the note of B (the 7th note of the scale).

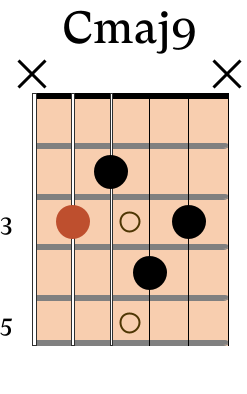

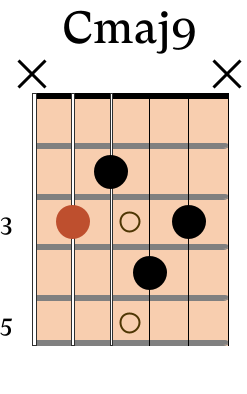

We can then take that Cmaj7 chord and turn it into a Cmaj9 chord by adding the note of D (the 9th note of the scale):

The foundation of the chord shape is the same, but now the note of D has been added into the chord on the B string – to bring more color to the chord and progression.

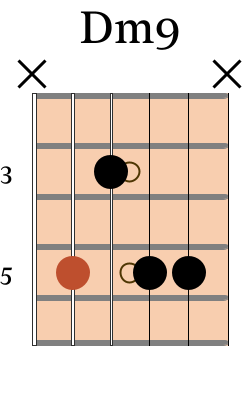

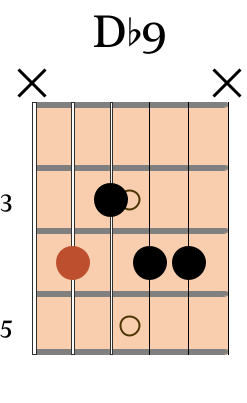

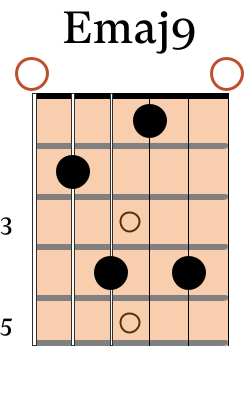

A Jazz ii-V-I Progressionwith Extensions

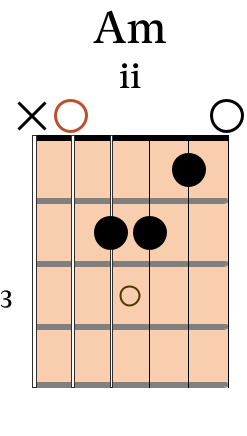

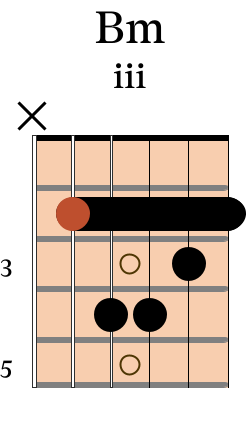

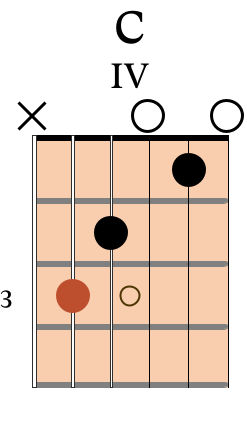

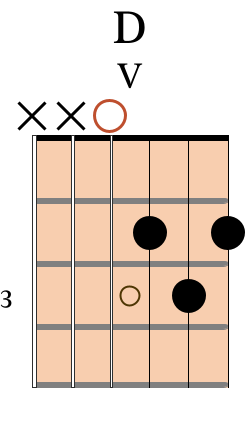

In jazz, you constantly see progressions like this:

This looks intimidating written out but in practice all we’re doing is building on simple foundations with added colors.

Concept 4: Pedal Tones (The Drone That Changes Everything)

Pedal tones (or pedal notes) are one of the most beautiful and practical concepts in music. The term comes from organ playing, where organists hold a bass note with their foot pedals while the harmony changes above.

On guitar, pedal tones create magical, shimmering textures that work across all styles of music.

A pedal tone is a note that keeps ringing through chord changes. The chords move underneath or around it, but that one note stays constant, creating a drone effect.

Pedal Notes in E Major

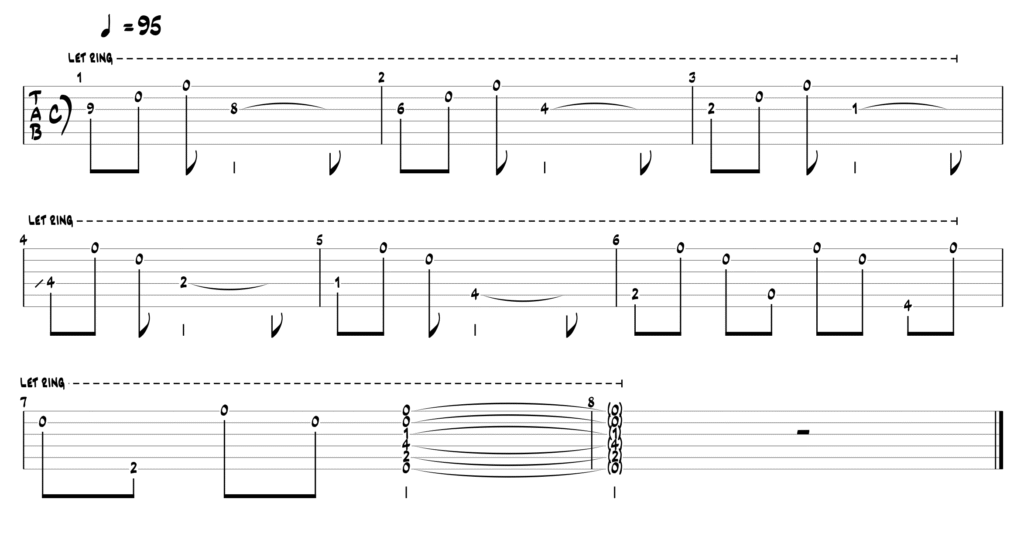

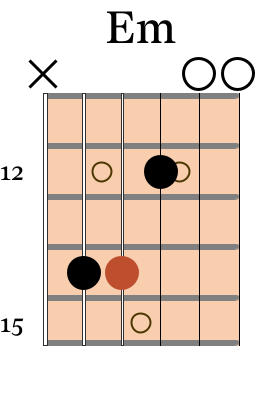

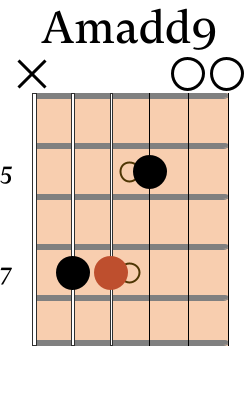

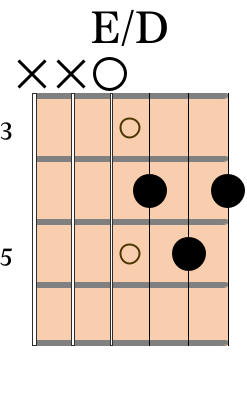

Here’s a classic guitar application. Play notes descending on the G string from fret 9 downward, while keeping the top two strings (B and E) open:

The open strings create a constant pedal tone while the harmony changes beneath them. This works beautifully in E major because the notes of both B and E are in the E major scale.

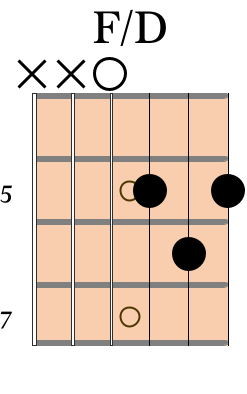

Pedal Notes in D Major

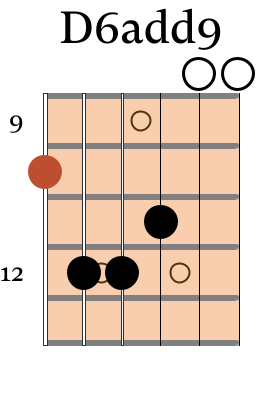

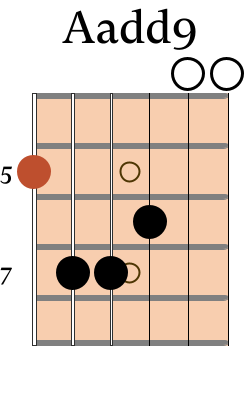

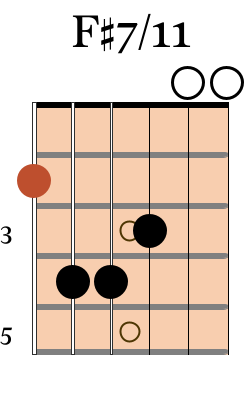

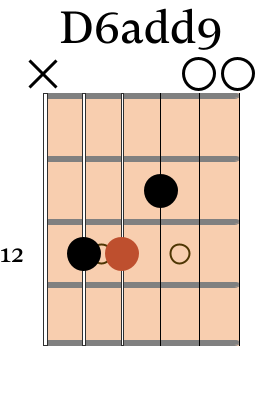

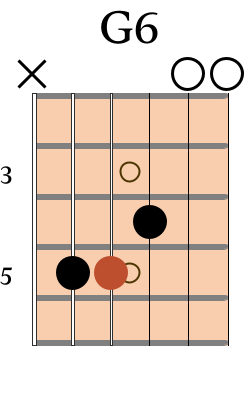

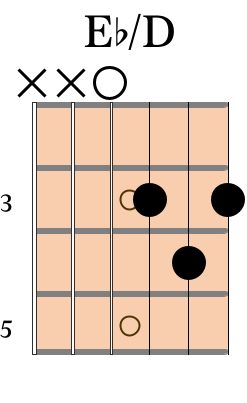

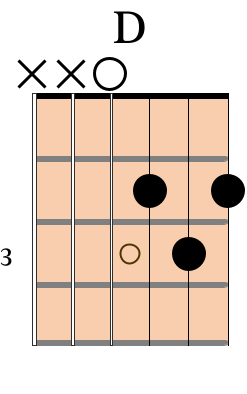

You can also use this in D major by play a D chord like this and letting the top two open strings ring:

From there you can then move through a number of chords that have the same shape, and in which the open B and E strings continue to ring out:

As you move through different chord voicings, those open strings add sparkle and create unexpected harmonic colors.

On some chords they’ll sound consonant (like normal extensions), while on others they’ll create beautiful dissonances.

Pedal Notes & Strumming

This technique also works wonderfully when strumming. You can play a sequence of major and minor triads on the lower strings while letting the high strings ring as a constant:

The contrast between the changing harmony and the constant pedal creates a hypnotic, contemporary sound.

Bass Pedal Notes

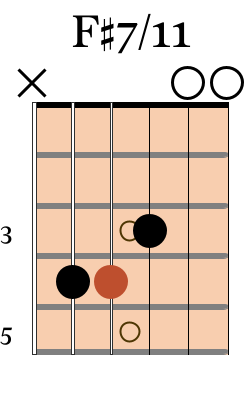

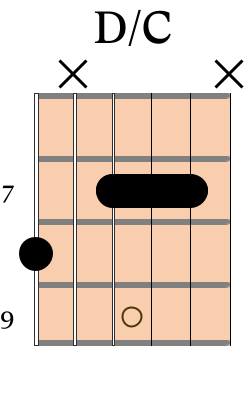

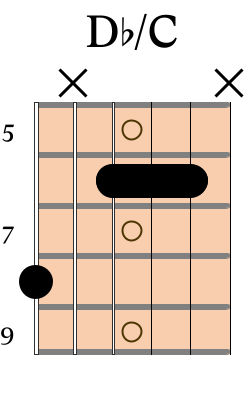

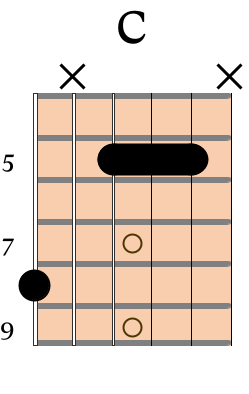

Pedal tones also work in the bass. This is common in jazz, where the bass note stays the same while chords change above it like this:

And you can also recreate the same idea using open strings, like this:

In both of these examples this creates smooth motion in the upper voices while the bass note of the chord remains the same.

Concept 5: Borrowed Chords (Stealing from Parallel Keys)

Borrowed chords are one of my favorite concepts in music theory — they’re the secret ingredient that takes a good progression and makes it unforgettable. When you want to create excitement, drama, or emotional impact—borrowed chords are your answer.

Let’s establish a simple progression in C major using the four chords we all know and love:

C major → G major → A minor → F major

These are all diatonic chords that occur naturally in the key of C major. And all of the chords that appear in the key of C major are as follows:

C – Dm – Em – F – G – Am – Bdim

These chords work well together because they all come from the same major scale.

However, if we want to create more interesting movement in our chord progressions we can “borrow” chords from the parallel minor – C minor.

The chords that appear in C minor are as follows:

Cm – Ddim – E♭ – Fm – Gm – A♭ – B♭

By borrowing chords from C minor while otherwise staying in C major, we create unexpected harmonic colors that add emotional depth.

The Classic Move: IV Minor

One of the most common borrowed chords is the minor IV chord. In C major, instead of F major, we use F minor (borrowed from C minor).

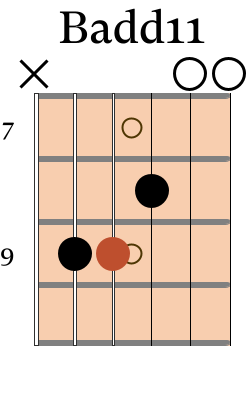

A great example of this would be the following progression:

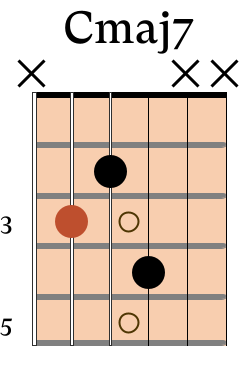

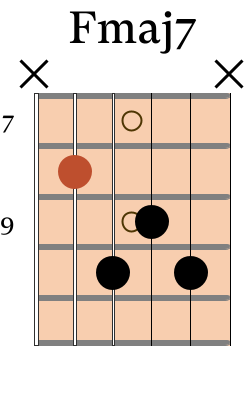

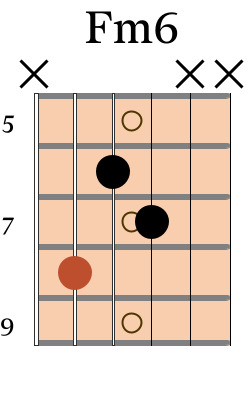

Cmaj7 → C9 → Fmaj7→ Fm6

This progression actually uses two of the concepts we’ve covered in this lesson!

Let me break it down:

- Cmaj7: Home base

- C9: Secondary dominant leading to Fmaj7 (concept 1!)

- Fmaj7 The diatonic IV chord

- Fm6 The borrowed iv chord from C minor

- Cmaj7: Resolution home

The movement from F major to F minor creates a bittersweet, melancholic color that’s incredibly satisfying. The minor iv chord adds darkness before the resolution.

This is just one example – but you can experiment borrowing a variety of chords from the parallel minor (as well as other parallel scales if you’d like!) to add different colors and interesting movements to your progressions.

Final Thoughts

Music theory concepts like these aren’t academic exercises—they’re practical tools that working musicians use every day. A pop songwriter uses borrowed chords to make a chorus more emotional. A jazz player uses secondary dominants to navigate standards. A fingerstyle guitarist uses pedal tones to create atmospheric textures.

Start experimenting with these concepts today. Pick one, try it in your playing, and listen to how it changes the music. Then move to the next one. Before you know it, these will become second nature, and you’ll wonder how you ever played without them.

The goal isn’t to use all five concepts in every progression—it’s to have them available in your toolkit when you need them. Sometimes a simple progression is perfect. Other times, you want to add that extra color, that unexpected twist, that moment of harmonic magic.

Now you have the tools to create those moments.

Good luck, and have fun experimenting!