I just got back home from seeing Paul McCartney play in Paris – absolute legend. And walking on the Champs-Élysées looking for a croissant and a coffee, well, it reminded me of a song.

Growing up, I loved punk rock, and “Champs Elysees” was one of my favorite NOFX songs at the time. But it was years later that I found out it was a cover.

The original song was by an artist called Joe Dassin, and the song was called “Les Champs-Élysées” – a song I recently heard again at the Olympics in Paris.

I thought, “That chord progression is just so nice.” I mean, the French – not only did you invent the perfect snack, but also this great, lovely-sounding chord progression!

Well, actually, it was a Dutch song. Okay, so we invented the stroopwafel and this beautiful song… or did we?

No, in fact all of these were covers of a song by a band no one has ever heard of: Jason Crest, and the song is called “Waterloo Road.”

This is the original, long-forgotten song that started it all.

Somehow it became that French anthem we all know today, and I think it’s partly because of that chord progression.

There are two very interesting things happening together that work in perfect harmony and create that lovely sound.

The Basics: Those Four Chords

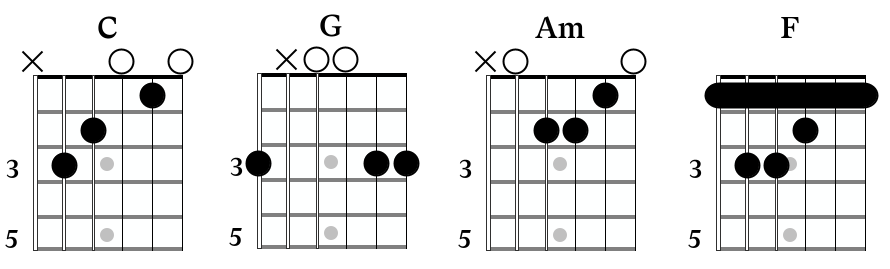

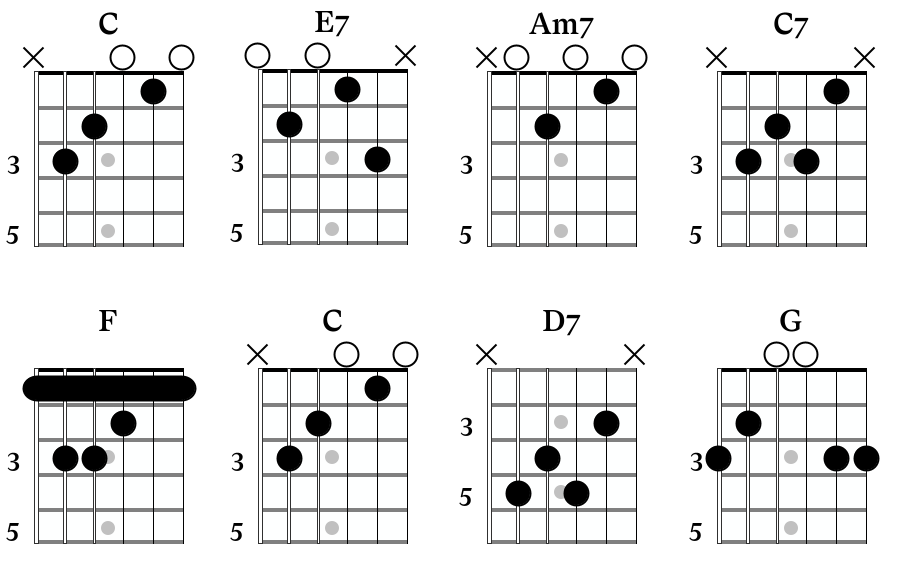

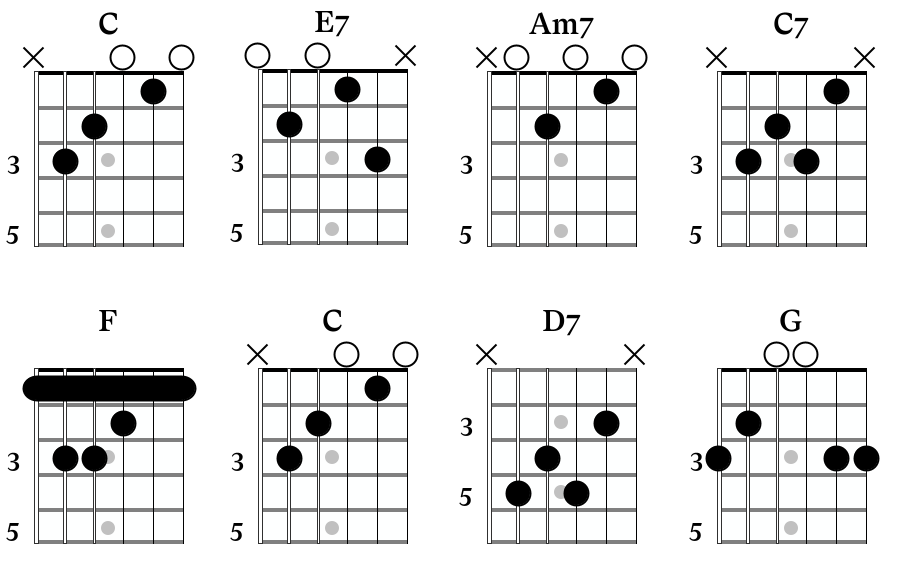

We all know those four chords you hear so often, right? This will sound familiar:

A big chunk of today’s pop music is written using just these chords. These are diatonic chords, and they sound easy on the ear. They will always sound good together, and if we rearrange them slightly into this order:

C → G → Am → F→ C → G

We find that the melody for “Les Champs-Élysées” will work perfectly over them.

But that’s not at all what is happening in reality in the song.

What’s Really Happening: Tension and Resolution

The chords are making a beautiful, satisfying movement—constantly creating tension and resolution—all while that bassline underneath (that so many seem to miss) connects everything beautifully.

Let’s break it down.

Part 1: Secondary Dominants (The Pivot Chords)

Starting Point: C to A Minor

First of all, we start on C and go to A minor. But we use a pivot chord to get to that A minor chord.

A wonderful chord to use as a pivot chord is a dominant chord of the chord you’re heading to. It’s a little bit theoretical, but if you hear it, it’ll make sense.

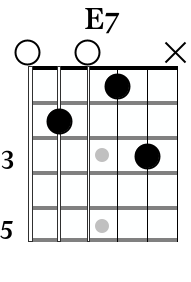

In this case, the dominant chord of A minor (the chord we’re going to) is E7:

We call this a non-diatonic chord and it sounds perfect if we place it between the C and Am chords. So now we have:

C → E7 → Am

That sounds just perfect, right? Super satisfying. We call this a secondary dominant, and it happens all the time in music.

Moving to F: The C7 Pivot

But what do we do next? The next line starts on the F chord:

Can we use a pivot chord to get to the F chord?

To find the dominant chord we need here, we just count five notes up in the scale: F – G – A – Bb – C.

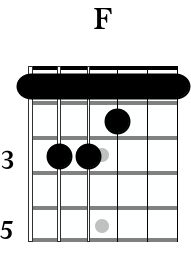

On that final note of C we can build a dominant seventh chord, which is C7:

If we put that C7 before the F it sounds just perfect! So now we have:

C → E7 → Am → C7→ F

Then after that F chord, we play the C and resolve to the G chord. Or do we?

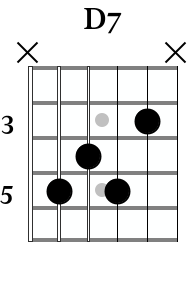

Getting to G: The D7 Pivot

Can we use a pivot chord to get to the G chord? Maybe? Why not? Let’s do it once more – two times is not enough!

The fifth of G (1-2-3-4-5) is D. So we end up with the chord of D7:

This D7 to G creates a super classic sound as it creates a II-V-I chord movement at the end of the chord progression. You’ll hear this in every chord progression out there, all of the time. II-V-I at the end. If you hear it once, you cannot unhear it.

The II-V-I chord movement explained:

- In the key of C, D is the second note or 2

- G is the 5

- C is the 1 (the homebase or tonic note)

So: D7 – G7 – C creates a classic resolution or turnaround that you will hear in a lot of chord progressions.

The Complete Progression (So Far)

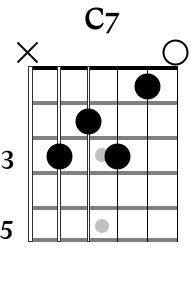

Let’s hear how satisfying this chord progression sounds in total. It’s so rewarding to play this:

The progression then loops back round to the beginning and it all starts again.

Part 2: The Descending Bassline (The Secret Sauce)

But this is only half of the story. I told you that the bassline ties everything together beautifully, right?

Inside the chords there lies a hidden line—a hidden bassline that helps connect all the chords so amazingly together. It’s the oldest trick in the book and one that you will hear in many, many songs.

The Line Between C and A Minor

In the beginning, where we used the E7 chord to go to the A minor chord—between the C and the A minor, is there a note that lies exactly between the C and the A?

C → ? → A

The answer: B

What you see so often is when you move between two chords, you connect them with the note that lies between them.

In this case the notes of C – B – A

We call this a descending bassline.

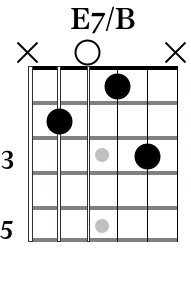

Making It Work: E7/B (First Inversion)

But how can we make that work in our chord progression?

That B note is also a part of the E7 chord we play!

So now we don’t play the low E as a bass note – we play the B as a bass note (the fifth of that E7 chord):

This is an inversion that sounds super amazing, right?

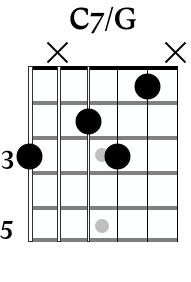

Extending the Bassline: C7/G

We can extend this approach across the chord progression.

The next chord is the C7, the pivot chord that leads to the F.

So if we were to continue that descending bassline, we would get: C – B – A – G

And if we put the G underneath the C7 with G in the bass then we end up with the following:

Again, it’s the fifth of the C7.

And we can continue this process as we move through the progression.

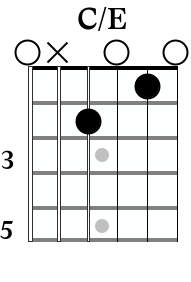

Continuing Down: F and C/E

After that C7, we go to F, which is again one note lower in the scale:

G → F

And then we go to C.

Below the F is an E, so can we somehow put the E in the C chord?

Of course! The E is the major third in the C major chord, and we can put that note in the bass, like this:

This creates a classic sound that I really love.

The Final Step: D7

I hate that the guitar runs out of notes here because we want to go even lower to that D chord when we go to the D7 (the II of the II-V-I).

We can’t hit that note in the lower registers, but by moving to that D7 chord we do continue the movement from E down to D.

Sadly, the descending bassline has to stop after that as we go to the G and then back home to C.

But what we have created is a descending bassline in the key of C major, just following the C major scale down:

C → B → A → G → F → E → D → G

The Complete Progression with Bassline

If we put all of that together, then we end up with the following chord progression:

Brilliant, right? I love it so much.

Why This Progression Works So Well

Let’s recap the two magical elements that make this progression irresistible:

1. Secondary Dominants (Pivot Chords)

Instead of moving directly between diatonic chords, we use dominant seventh chords to create tension and resolution:

- E7 → Am

- C7 → F

- D7 → G7 → C (The classic II-V-I)

These non-diatonic chords add sophistication and forward motion to the progression.

2. Descending Bassline (Stepwise Motion)

The bass notes descend stepwise through the C major scale:

C → B → A → G → F → E → D

This creates smooth voice leading and adds a beautiful sense of coherence to the progression.

When you combine these two elements – the harmonic tension of secondary dominants with the melodic smoothness of the descending bassline – you get a progression that’s both sophisticated and singable. Just wonderful!