There’s this chord progression in Bob Dylan’s “Make You Feel My Love” that uses a trick that makes it so wonderfully beautiful and sad at the same time.

And once you hear it, you cannot unhear it. It magically ties all of the chords in this progression together.

Let me show you how he does it.

Understanding Diatonic Chords: The Foundation

The vast majority of songs you hear on the radio are made up of just a handful of chords. These are typically diatonic chords – which are the chords that are formed when you turn the notes from the major scale into chords.

You can actually see it super easily on a piano. If you just play the white keys, you get the C major scale. And if you want to make a chord out of this, well, you play one, you skip one, you play one, you skip one, and you play one.

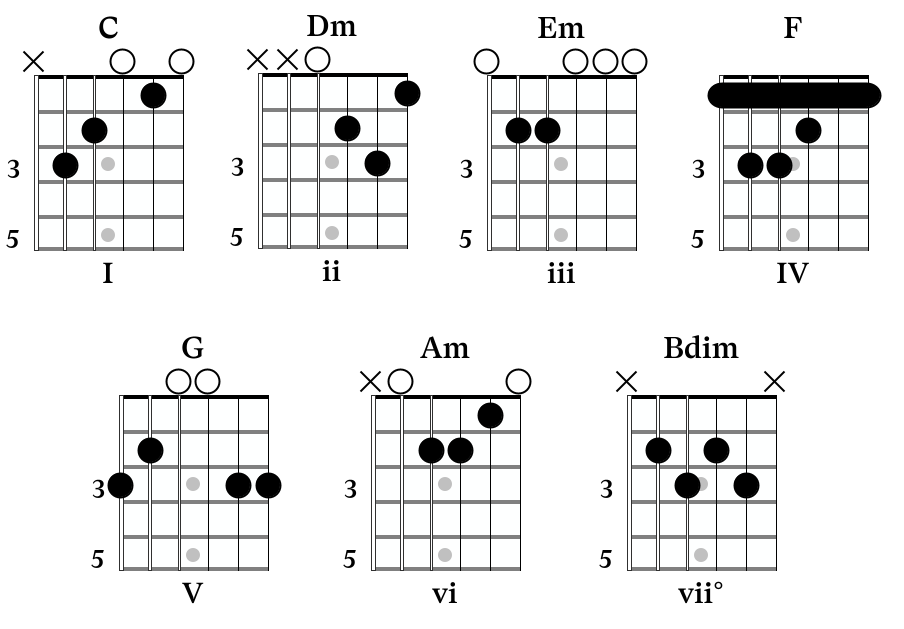

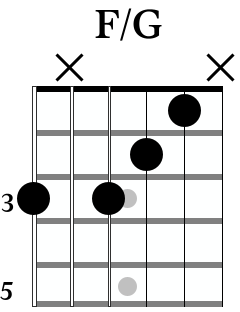

On the guitar, here are the diatonic chords that are created when you harmonize the notes of the C major scale:

We take these chords as a starting point and can then change them to create more varied and interesting progressions.

“Make You Feel My Love”

That is exactly what Bob Dylan does throughout the song “Make You Feel My Love.” You might know this song from Adele, but it was Dylan who wrote it, and now we’re going to dive into it in a bit more depth, because it really is wonderful.

If you want to match the key of Bob Dylan’s original recording, put a capo on fret 1 and play everything the same. For now though, let’s stick to C major to make the theory a little clearer.

The Verse Progression: Where the Magic Happens

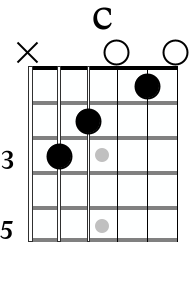

Chord 1: C Major (The Tonic)

We start out with C major—the home chord, the tonic:

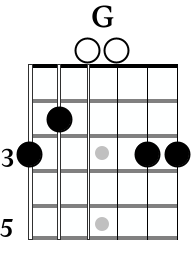

Chord 2: G/B (First Inversion Magic)

Then the progression moves to G major, which is the the V chord (five chord). This is a I to V chord movement that takes us from the tonic to the dominant chord:

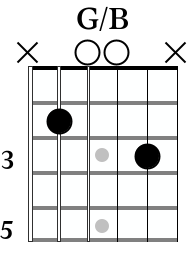

From there we can put the note of B in the bass of the chord, which works very well and sounds amazing after playing the C chord. The inversion of that G chord looks like this:

This movement from the C chord to the G/B sounds so beautiful, because the semitone movement from C to B really connects the chords beautifully together.

This is the beginning of our line cliché – so pay attention to that descending bassline as we move through the rest of the progression.

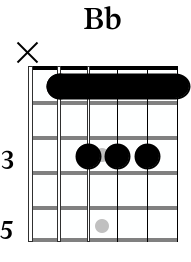

Chord 3: B♭ Major (The Borrowed Chord)

After that G major, we jump to an odd chord. And here the magic starts for me, at least. It’s a B♭ major:

This is a non-diatonic chord as it doesn’t appear when we harmonize the notes of the C major scale.

When we add this chord into the mix, we move from:

C → G/B → Bb

This creates a beautiful and melancholic sound, for two main reasons:

First: This chord is a so-called borrowed chord from C minor. We call this modal interchange – where we use chords from different modes or parallel keys. Although the chord is from a different mode, that B♭ still has one note in common with the previous G major chord. The D and G we had in G major—we also have that in B♭. And that’s why the chord movement sounds so nicely connected.

Second: We actually extend that semitone line we had going from C to B to B♭, which is also a strong connection to the chords before.

And interestingly, Bob Dylan chooses to sing that same note he sang over the C chord – the high G – but over the B♭this basically turns the B♭ into a B♭6 chord because the G is the sixth note in B♭.

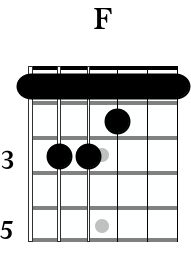

Chord 4: F Major (The IV Chord)

From there, Bob Dylan jumps to the IV chord, which in the key of C is F:

Again, we have a shared common tone between the chords. The F is in B♭, but also in F major.

We’re also extending that semitone descending line – now hitting the note of A, which is the major third from the F chord.

This descending line so far: C → B → B♭ → A

How cool is this?

The Line Cliché: The Secret Sauce

This phenomenon actually has a name. It’s called a line cliché. “Cliché” because it’s the oldest trick in the book.

You hear this technique everywhere – in “Stairway to Heaven” by Led Zeppelin, in “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” and “Michelle,” by The Beatles, and in countless other classics. It’s wonderful.

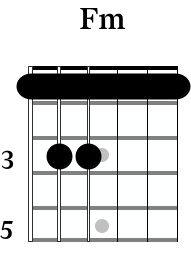

Chord 5: F Minor (The Minor iv)

From here we move to the minor iv chord.

There’s a whole subreddit dedicated to this legendary chord movement. There’s a Spotify playlist containing songs featuring this change. It’s a classic.

In a major key – like C major – you would normally play a major IV chord. So in C, you would play an F major chord.

However, Bob Dylan changes this here, instead moving to play F minor:

That F minor is also a non-diatonic chord – a borrowed chord from C minor. And if you move from F → Fm → C it sounds wonderful and creates a beautiful sense of movement and resolution.

But listen to it when I play it in this tune, because it doesn’t feel like a resolution yet. It’s the start of a second round of chords, and we need to put an end to this. We need to circle back home.

The Turnaround: Getting Back Home

We do this by playing a little turnaround that concludes this beautiful first progression. And it doesn’t get more classic than this: II-V-I (2-5-1) chord movement.

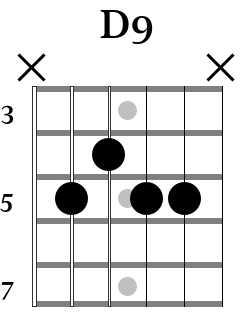

Chord 6: D9 (The Secondary Dominant)

The ii chord in this case would be a D chord – and in the diatonic framework it would be a D minor chord.

However Bob Dylan turns this into a secondary dominant chord. We’ll play it as a D9, because Dylan sings the note of E in the melody, highlighting the note of E:

We call this chord a secondary dominant because it doesn’t resolve to the tonic. It resolves to another chord within the key – in this case, to the V chord.

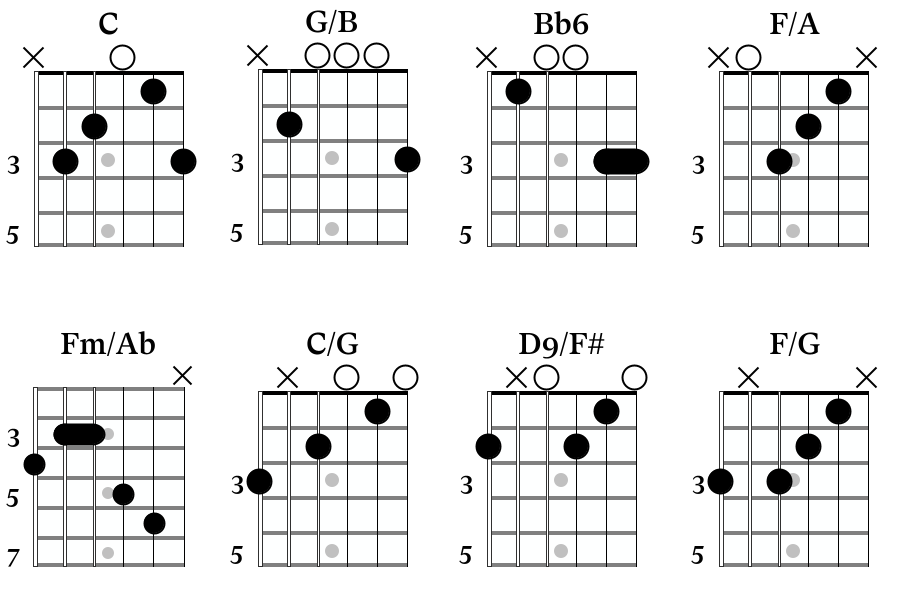

Chord 7: F/G (The Sus Sound)

We don’t now move to just any V chord. What we resolve to is what I always used to call a “sus chord” – the Gsus. But the definitions vary, so it might be safer to stick to F/G.

We play an F triad and we put a G in the bass. This is what the chord looks like:

This somehow has a bit of an ambiguous feel. We almost have the plagal cadence, which is the chord movement from the IV to I (F to C). But then because we put the G in the bass the chord also gives us a dominant sound – it’s super nice.

So in this section we move from:

D9 → F/G → C

And when we put that together with the initial chords we covered, we end up with:

C → G/B → Bb → F → Fm → C → D9 → F/G → C

Beautiful!

The Complete Line Cliché Revealed

But wait a second. Do you remember that semitone line, the line cliché we talked about in the beginning? In the intro, I said there’s one thing that ties all the chords together.

Well, you know what? We can keep that line cliché going and going and going for the entirety of this chord progression.

With every chord change, we go down one semitone – hitting the white keys, the black keys, all of them. The chromatic scale goes down from C all the way to E like this:

C → B → Bb → A → Ab → G→ F# → F → E

The note of C is in the C major chord, the B is in the G/B chord, the Bb is in the Bb chord, and so on.

That line – which is almost hidden in the chord changes – really connects all of the chords together. It makes them sound coherent and gives the whole piece a very melancholic feel at the same time.

Putting the Line Cliché in the Bass

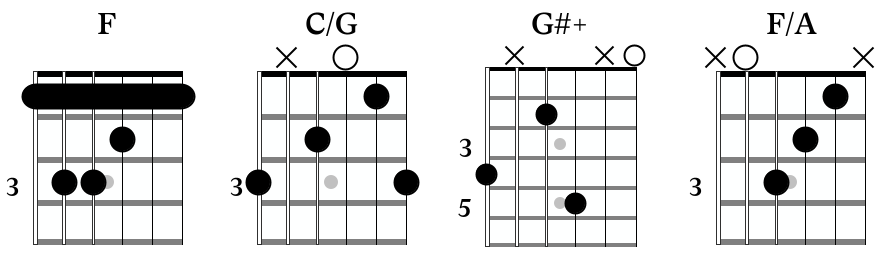

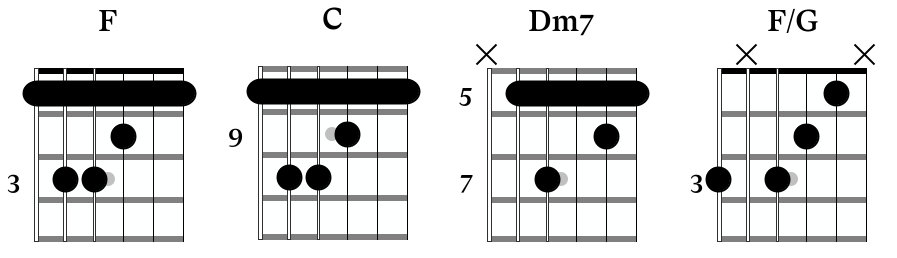

What’s super fun to do is to use that line cliché and put it in the bass of the chords in the progression. I heard one recording where the bass player did that, and it sounds amazing. We can do this on just the guitar by using the following chord voicings:

From that F/G you can then bring it all to a lovely conclusion by playing the C.

And there we are. We put the line cliché in the bass. And you can keep that going through the whole song.

The Chorus: One More Perfect Chord

The focus of this lesson is on the verse in this song. But in the chorus, there’s one chord that is so perfect that I wanted to run through this part quickly too.

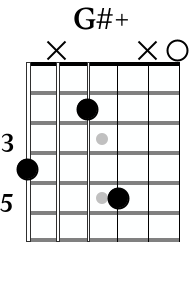

The Augmented Chord Magic

The chorus starts on an F chord – the IV chord – and then it moves to the I chord (the C but with a G in the bass)

So we have F→ C/G

And then the third chord arrives – the G♯+:

This is an augmented chord, which contains a major third and where the fifth is raised a semitone.

So we also have that line cliché going on, but then in the opposite direction – it goes up! Because when we go from that G♯ augmented, we go to the IV chord, to F again, but now with an A in the bass.

So we have this ascending line:

G → G♯ → A

When we put those chords in the chorus together, we end up with the following:

After the F/A the progression briefly moves to the C chord, before going into a second round. This time though, things change slightly as we use the following chords and voicings:

As before, after the final F chord (this time with G in the bass), the progression moves to C, where it resolves.

Why This Matters for Your Playing

There are many, many cool things happening in this tune. It’s so subtle, but if you hear it, you cannot unhear it. And that’s the beauty of these types of chord progressions, which you’re going to encounter over and over again in so many different songs. Once you recognize these patterns, you’ll start noticing them everywhere:

- The descending chromatic bass line appears in countless songs

- The minor IV chord is a staple of emotional songwriting

- Borrowed chords add color and depth to otherwise simple progressions

- First inversions create smooth voice leading between chords

These aren’t just theoretical concepts. They are practical tools you can use in your own playing, whether you’re arranging covers or writing original music.

Final Thoughts

“Make You Feel My Love” is a masterclass in sophisticated simplicity. The chord progression uses borrowed chords, line clichés, and classic movements to create something that sounds both familiar and deeply moving.

The beauty is in the subtlety. Once you hear that descending chromatic line connecting every chord, you can’t unhear it – and that’s exactly the point. These techniques work because they tap into something fundamental about how we perceive musical motion and emotion.

Every time you play through this progression, you’re using tools that have been refined over centuries of musical evolution. And the best part? These same techniques are available for you to use in your own musical journey.