I’m going to make a bold claim: the next five minutes could be the most valuable time you ever spend with a guitar. And no, this isn’t hyperbole.

Shell chords are a technique I use constantly – in shows, recording sessions, jam sessions, and when learning and writing new songs. Once you understand this concept, you’ll be able to play virtually any song, using just a handful of chord shapes.

The best part? You can genuinely learn this today.

This isn’t something you’ll start on today and master in five years, you can learn these shell voicings quickly and start using them immediately in your playing.

The Problem with Traditional Chord Voicings

Picture this: You’re looking at a chord chart and see something like “Cm7♯9♭13” and think, “What am I supposed to do with this?” Or you’re playing with other musicians and struggling to voice chords that don’t clash with the bass player or sound too cluttered in the mix.

This is where shell chords come in. They’re the solution to complexity, the key to reading any chart, and—most importantly—they actually sound great.

What Are Shell Chords?

Shell chords are a reduction of full chord voicings down to their absolute essentials: the notes that define the chord’s character.

So instead of playing five or six strings, you’re playing just three carefully chosen notes. These notes are as follows:

- The Root (1): Establishes what chord you’re playing

- The Third (3): Tells you if it’s major or minor

- The Seventh (7): Reveals whether it’s a major 7th (home, resolved) or flat 7th (tension, wanting to move)

Notice what we’re not playing? The fifth.

The fifth doesn’t add that much color or “information” to each chord, and by leaving it out, we can create cleaner voicings that have more space for melody and other instruments.

The seventh is the secret sauce here, as it provides a lot more harmonic information and adds a new and distinctive flavor to the chord. For example, an A major 7th sounds lush and complete – like home. An A7 (dominant 7) creates tension and wants to resolve somewhere.

The Four Essential Shapes (5th String Root)

Let’s start with shell chords with their roots on the 5th string. There are only four shapes you need to learn, and they’re all closely related, so you can easily move between each chord shape with only a small change in fingerings.

All of our examples here are based around C chords – showing how small changes to these chord shapes can totally alter their sound.

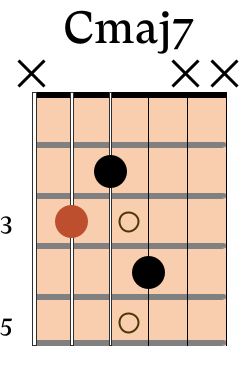

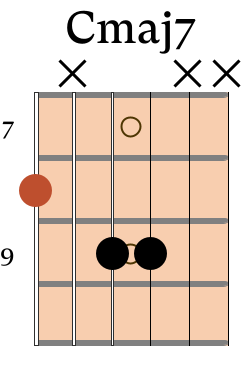

Shape 1: Major 7

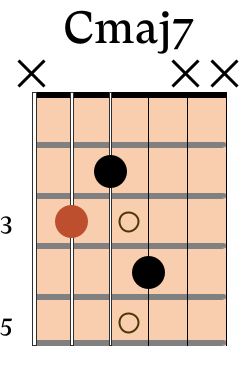

First up we have C major 7 – a beautiful voicing that has a sophisticated and “jazzy” sound, but one that is not overly complex.

The root note of the chord (the C) is shown in red with the two remaining notes of the chord (the E and B) shown in black. Listen to how the chord sounds and the distinctive flavor that it creates.

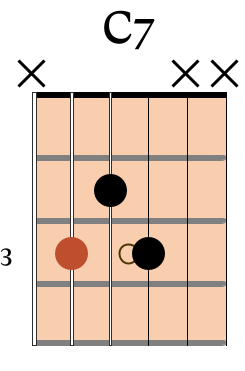

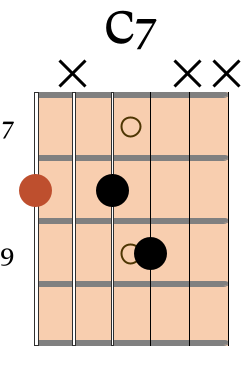

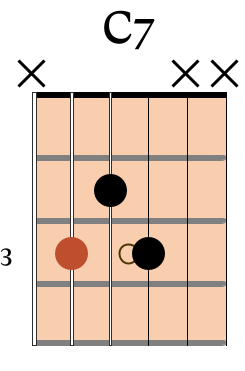

Shape 2: Dominant 7

From major 7, simply move your finger on the 7th (the note of B) down one fret (one half-step) and now you’re playing a C7—a dominant seventh chord.

Notice how the character of the chord changes completely? This chord has tension. It wants to resolve somewhere, typically down a fifth (in this case, to F).

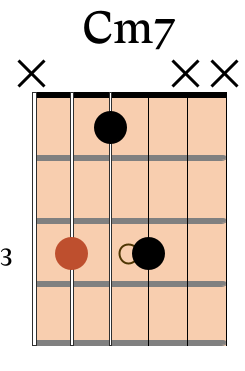

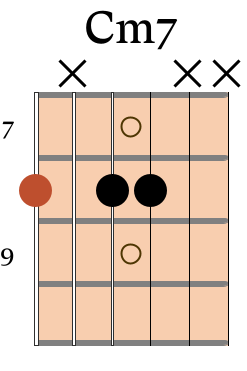

Shape 3: Minor 7

By targeting a similar movement and shifting the 3rd down one fret (one half-step), you’re now playing C minor 7.

As the stretch here increases, you can choose to play the notes on the third fret with either your middle and ring fingers, or your ring and little fingers – use whatever feels most comfortable for you.

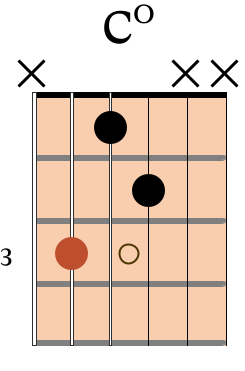

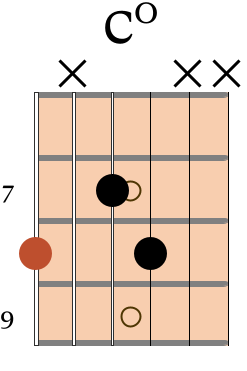

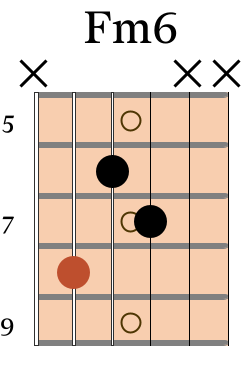

Shape 4: Diminished / Minor 6

Our next chord shape can perform two functions . Technically it’s a diminished chord, but it functions identically to a minor 6 chord—and in practice, you might treat this shape more frequently as a minor 6 chord in your playing. It looks like this:

In minor keys, using a minor 6 chord instead of minor 7 for the tonic sounds more stable and resolved. That’s why you’ll see this in jazz standards like “Summertime.”

Real-World Application: “Summertime”

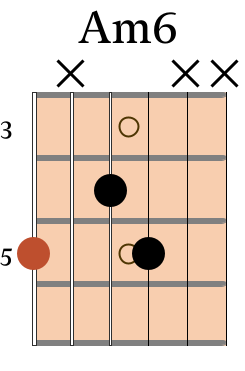

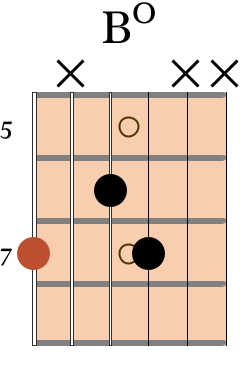

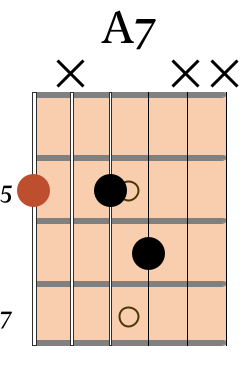

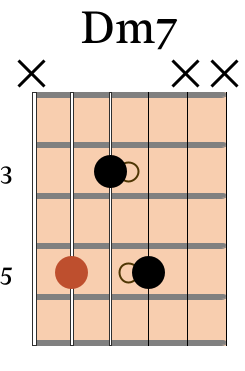

We can use these chords practically with the song Summertime by George Gershwin, which uses the following chords in the opening progression:

These are played together in the following order:

Am6 → B° → Am6 → A7 → Dm7 → F7 → B°→ E7 → Am6 → B° → Am6 → Dm7 → G7 → Cmaj7 → B° → Am6

In this specific piece, the progression is centred around an A minor 6 instead of an A minor 7.

This is important because it establishes A minor as “home.”

If we played A minor 7, it would sound like we’re heading somewhere else – down to the G major. The minor 6 sounds resolved and stable, which is exactly what we want for the tonic.

The Four Essential Shapes (6th String Root)

Once you’ve got the 5th string shapes down, learning the 6th string versions is quick because the concept is identical.

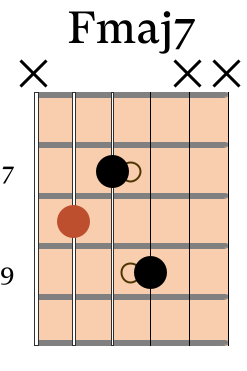

Major 7 (6th String Root)

If you know a standard C major barre chord, you already know most of this shape – you just need to remove the 5th interval:

Dominant 7 (6th String Root)

Move the major 7th (B natural) down to a flat 7th (B flat) on the D string and you end up with a C7 chord:

Minor 7 (6th String Root)

From this dominant 7th chord shape, you can flatten the third and create a minor 7 chord by moving your finger one fret lower on the G string:

Diminished / Minor 6 Chord (6th String Root)

The final shape built with its root on the 6th string can again function as both a diminished chord or minor 6:

Adding Extensions With Shell Chords

One of the biggest benefits of learning these shell chords is that it makes adding extensions to chords easier.

Looking at chord charts and seeing chord names like Cm7♯9♭13 can be intimidating. But if you start with the shell, it makes targeting those extensions a lot simpler.

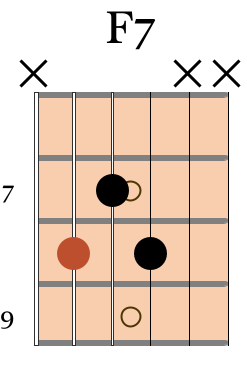

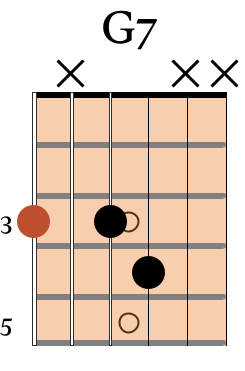

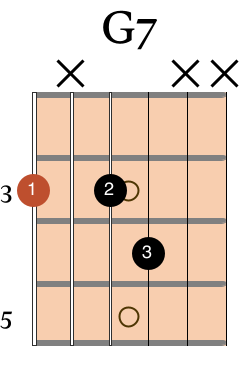

For example, if we play a G7 chord built on the 6th string, we would use the following fingerings:

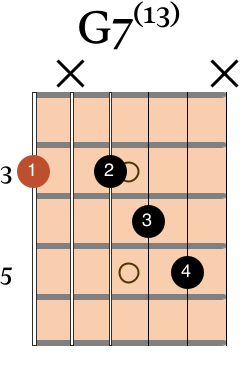

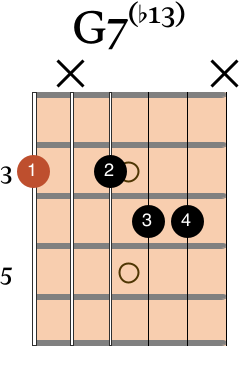

With only 3 notes in the chord, you have your little finger free to add extensions to the chord. And by just adding a single note, you can create a further variety of beautiful voicings, like these:

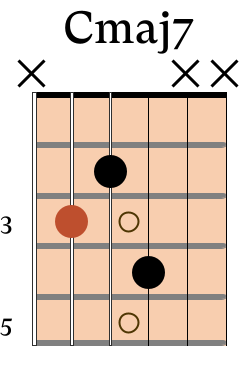

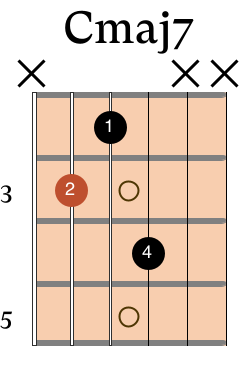

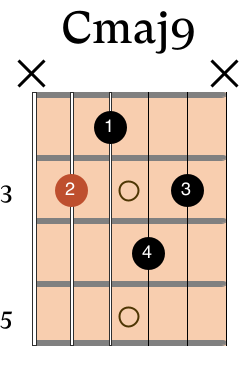

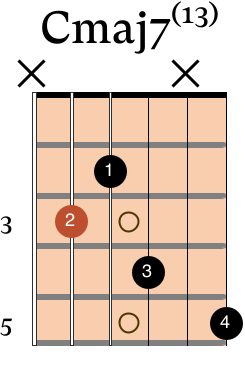

The exact same idea can be applied to the Cmaj7 chord. If we start with the first voicing that we used – with the root built on the 5th string, the fingerings for the chord would look like this:

However by adding a single note, we can create a variety of new chords, like this:

Once you start to appreciate the relationship of other notes to these chords you can play the melody on top of your chord voicings, creating solo guitar arrangements and improvising with greater freedom.

A Practical Jazz Progression

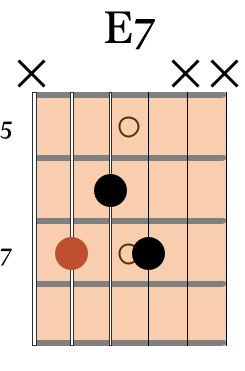

Using just these chord shapes we can create a typical jazz progression that sounds sophisticated, but which actually uses just four chords:

This progression works beautifully because:

- We’re using smooth voice leading (minimal hand movement between chords)

- Each chord has a distinct color

- There’s room to add rhythmic interest or melodic embellishments

- It sounds beautiful and sophisticated without being complicated

Learning these shell chords will provide you with a new way of thinking about the guitar.

You’re not memorizing hundreds of chord shapes anymore. You’re understanding how chords work and applying that knowledge anywhere on the neck.

Learn these shell chord shapes today and use them for the rest of your life.

Good luck, and have fun!