Mike Dawes is a master of creating entire band arrangements on a single acoustic guitar. When you watch him perform, you hear what sounds like multiple instruments—bass, drums, chords, and melody—all happening simultaneously. The secret? A combination of DADGAD tuning, innovative technique, and years of careful compositional practice.

Today I’m breaking down Mike’s approach to solo guitar, focusing on why DADGAD is the most approachable altered tuning for this style, the essential chord shapes you need, and how to layer multiple musical elements into one coherent performance.

The Philosophy: Six Pianos, Not One Guitar

Mike’s entire approach stems from a formative realization: “My electric guitar got broken and was laying on the table being glued, and I was looking at it thinking, ‘This is actually six pianos.’”

This perspective shift changed everything. Instead of seeing the guitar as one instrument with six strings, he began seeing it as six independent chromatic keyboards. Each string could play its own melodic line, creating the possibility of true polyphonic arranging.

But standard tuning presents a challenge: the chord shapes we learn are “fixed and rigid,” living in boxes and barre chord patterns. To facilitate playing multiple independent parts, Mike needed a tuning system that made complex voicings more accessible.

Why DADGAD Is Perfect for Solo Guitar

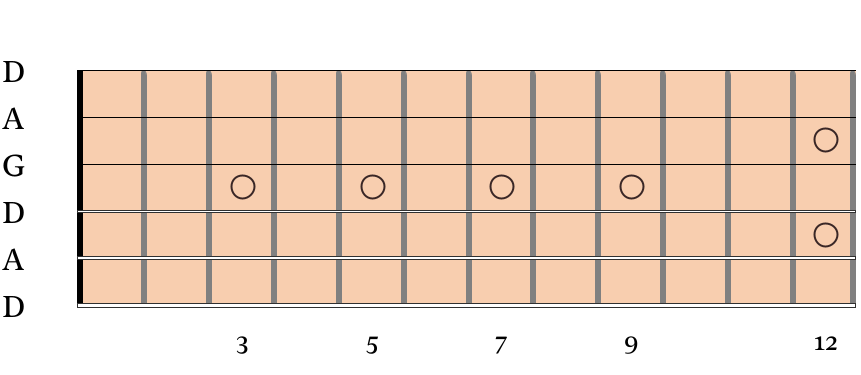

DADGAD tuning (D-A-D-G-A-D, low to high) is what Mike calls the most approachable tuning for playing in this multi-layered style:

It’s an open tuning: The open strings form a Dsus4 chord, which has a beautiful and open quality

It facilitates easier voicings: Notes that would require difficult stretches in standard tuning become much more accessible.

It provides sympathetic resonance: When you play in the key of D, all of those open strings resonate sympathetically, creating a fuller, richer sound.

It’s neither major nor minor: The sus4 quality means you can easily add either a major or minor third, making it flexible for any emotional color.

Tuning from Standard to DADGAD

If you’re in standard tuning (E-A-D-G-B-E), here’s how to get to DADGAD:

6th string (E): Tune down one whole step to D

5th string (A): Keep at A

4th string (D): Keep at D

3rd string (G): Keep at G

2nd string (B): Tune down one whole step to A

1st string (E): Tune down one whole step to D

Strum the open strings and you’ll hear a beautiful Dsus4 chord—neither major nor minor, but present and open.

From there, you can then create a range of chords with very simple fingerings:

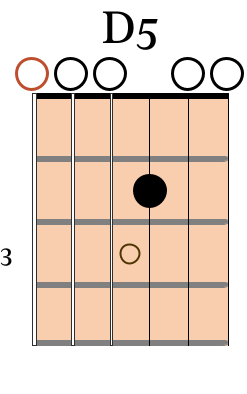

The D5 Power Chord

In DADGAD, a D5 power chord is remarkably easy. All you need to do is put one finger on the second fret of the G string, like this:

This turns the Sus4 sound of the DADGAD tuning into a massive sounding power chord that fills the room with sound because of all the doubled roots and fifths.

It’s all about”giving it the beans” as Mike would say!

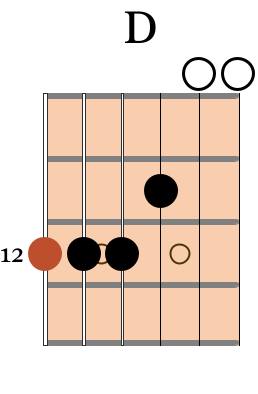

The Essential Movable Shape

The most important shape Mike uses – and one that appears in countless songs – is what he calls his movable “bar chord” shape, but with a twist:

This specific example shows a D major chord played at the 12th fret.

However Mike treats this chord shape like a barre chord that can be moved anywhere. The key is that the top two open strings bring different colors into the chord, and this changes the quality of the chord when you move the shape around the neck.

Try moving the shape around the fretboard and listen to the unique quality of each chord, as the relationship between the fretted notes and open strings changes.

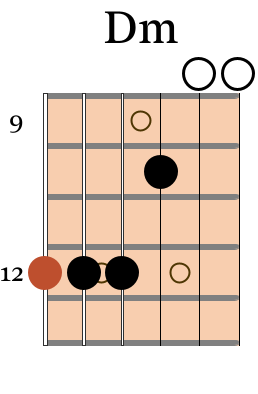

Making It Minor: The One-Fret Adjustment

Here’s where DADGAD becomes truly flexible. To make any of these major type chord shapes minor, you just need to move the note on the G string down a single fret.

So if we take our D major chord shape from above, we can turn it into a D minor chord like this:

This again is a movable shape – and allows you to play beautiful major and minor progressions across the entire neck of the guitar.

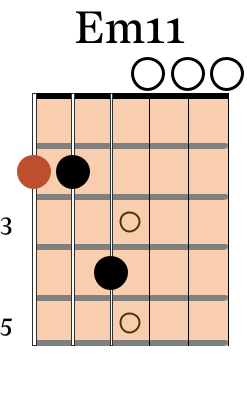

The Fourth Essential Shape: Minor 11

The other crucial chord shape creates a slightly spicier sounding chord – an Em11:

As with all of the chord shapes covered so far, you can shift these around the neck, creating different harmonic flavors with the open strings providing color.

Music Theory for Alternate Tunings

If you are used to playing in standard tuning, then playing these new chord shapes and picking out melodies in DADGAD might feel awkward.

Mike’s recommendation here is to take a pragmatic approach and focus on interval training:

“In a wacky tuning, everything’s reset. Interval training makes figuring out where you are quicker because I’m not looking at the fretboard visually in terms of shapes—I’m fooling around and finding out. The finding out is easier if you understand the relationship between the notes you’re hearing.”

Try not to overthink which intervals you’re playing, and instead let your ear and fingers guide you to where the notes are and the quality of those notes.

Creating the Four-Layer Sound

Beyond these beautiful chords, Mike’s signature technique involves layering four distinct musical elements:

- Bass line

- Chord voicings

- Melody

- Percussion

The key is giving each layer its own distinct character so listeners can follow each part independently.

Layer 1: The Bass Line

The bass is played with the fleshy part of the thumb, not the nail. This creates a warm, rounded attack that sounds like an actual bass guitar.

Mike emphasizes: “I’m trying to play with the attack of a bass player – more meat, not picking it with a fingernail.”

The bass line is often played legato (notes flowing together), providing a smooth foundation.

Layer 2: The Chords

Mike often plays his chords with a hammered attack, giving them a percussive energy that distinguishes them from the bass.

Sometimes chords are strummed, other times they’re picked as arpeggios. The key is maintaining a consistent character that makes them recognizable as chords, not the melody.

Layer 3: The Melody

Melody notes are often played staccato (short and detached) to make them stand out from the sustained bass and chords.

Mike uses right-hand muting to achieve clean staccato:

“If you mute with the left hand, you get a little chord ringing through. But if you mute with the right hand, there’s more control—super clean.”

The melody can be played with:

- Standard picking

- Harmonics (natural or artificial)

- Hammer-ons and pull-offs

Each technique creates a different tonal character, giving the melody its own voice.

Layer 4: The Percussion

The percussion comes from striking the guitar body—specifically, the area Mike describes as the “sweet spot.”

“If the end of the sound hole and where the bottom string meets the bridge were two points of a triangle, the third point is the sweet spot.”

The basic technique:

- Kick drum: Hit with the palm of the hand near the sweet spot

- Snare: Slap with fingers on the strings or body for a sharper attack

Mike’s signature Andreas Cuntz guitar has reinforcement in this area specifically to withstand the percussive attack.

The Composing Process: Melody First

When it comes to putting these layers together and composing a piece or creating an arrangement, Mike’s philosophy is to start with the melody first and then build in the other layers:

Step 1: Compose or learn the melody

Step 2: Add bass notes to give it harmonic home

Step 3: Elaborate the bass line

Step 4: Fill out chord voicings

Step 5: Add percussion

The idea is not to “cram every technique in there for the sake of it” but to create a piece of music in which every musical layer has its own voice and sounds like a different instrument.

Mike illustrates what this looks like in the interlude for the track “Somebody That I Used to Know,” where he demonstrates how he plays the bass line with the pad of his thumb to create a warm attack and a legato feel. He then uses hammer ons when playing the chords of the piece to create a more staccato, percussive sound.

Creating Loops Without a Looper

Creating these distinctive musical layers allows Mike to create loops without a looper.

In his song “Cloud Catcher” for example, he creates what sounds like a looped pattern, but it’s all played in real-time without electronic looping:

The bass line is played in a muted and percussive style. The chords are played using hammer ons, and the melody is picked out on top of that.

Each element becomes like a different member of the band and your ear is able to pick them out as independent layers, even though they’re all being played on a single instrument.

Closing Thoughts: Write Music, Not Technical Displays

Mike’s final wisdom: “I’m trying to play a tune at the same time. I have plenty of songs that do all the technical stuff, but the best stuff comes when you write intuitively with melody and harmony first.”

The goal isn’t to show off how many things you can play simultaneously—it’s to create music that sounds like a full band while being playable by one person.

DADGAD tuning is the gateway to this approach, providing a foundation that’s simultaneously simple to learn and infinitely deep to explore.

Start with the basic shapes, add one layer at a time, and before you know it, you’ll be your own backing band.